Curriculum Units as Storytelling

Netflix’s Stranger Things logo from wikipedia.org

Rewatching Netflix’s Stranger Things

My daughter and I were a little late to the Netflix TV phenomenon of Stranger Things. We didn’t join the fan club until the summer of 2019 and the release of season 3. At that point, before we could watch season 3, we had to go back and watch the earlier two seasons. We were both immediately hooked; it was such a compelling story of everyday, small-town people, including a bunch of pre-teens on BMX bikes, battling supernatural forces from the Upside Down that they associate with creatures from Dungeons and Dragons. It didn’t hurt that the setting for the series is the fictional small town of Hawkins, Indiana, a town not dissimilar to Danville, Indiana where my wife’s parents lived and where we were visiting for the summer. Though a little lost on my daughter, the 1980s nostalgia of the series also appealed to me. If you were to sign into our family Netflix account, you’d find that our profile images to this day are different characters from Stranger Things. You probably wouldn’t be surprised that my profile is represented by Jim Hopper, the paunchy, rumpled, middle-aged, dad-ish, Hawkins chief of police.

In anticipation of the release of the first part of the final season later this month, I’ve been rewatching the earlier seasons recently. As one would expect, each season of Stranger Things follows its own narrative arc. At the start of each season we’re introduced to the main characters, the setting time and place, and background information connecting it to the previous season. There is also foreshadowing of the conflict to come that hooks the viewer. The season then proceeds by revealing the conflict of that particular season, which always involves some sort of evil breach from the Upside Down into the town of Hawkins. The rising action continues one episode after another until the season reaches a climax where the protagonists must do battle with the Upside Down to rescue friends, save Hawkins, and prevent the destruction of their 1980s America dimension. The season then concludes by resolving loose ends, bringing everyone back together, and teasing the next season.

Okay, now for a screeching 180 degree turn– but bear with me, it does relate.

Heidi Hayes Jacobs and Curriculum Storyboarding

While rewatching Stranger Things this week, I’ve also been reading about the curriculum work of Heidi Hayes Jacobs. In an interview that I watched, Jacobs explained that she used to tell her students at Columbia University’s Teachers College that when they signed up to take her curriculum design course, they were really signing up for a creative writing course. By this she meant that creating curriculum was like writing a story. There is a beginning, a middle, and an end, there is a challenge or conflict, there is rising action, there is a connecting through-line, there is a climatic moment, and there is some sort of denouement or resolution. In addition, there are big ideas and themes that should leave a lasting impression on the students, helping them to make sense of the world in some way.

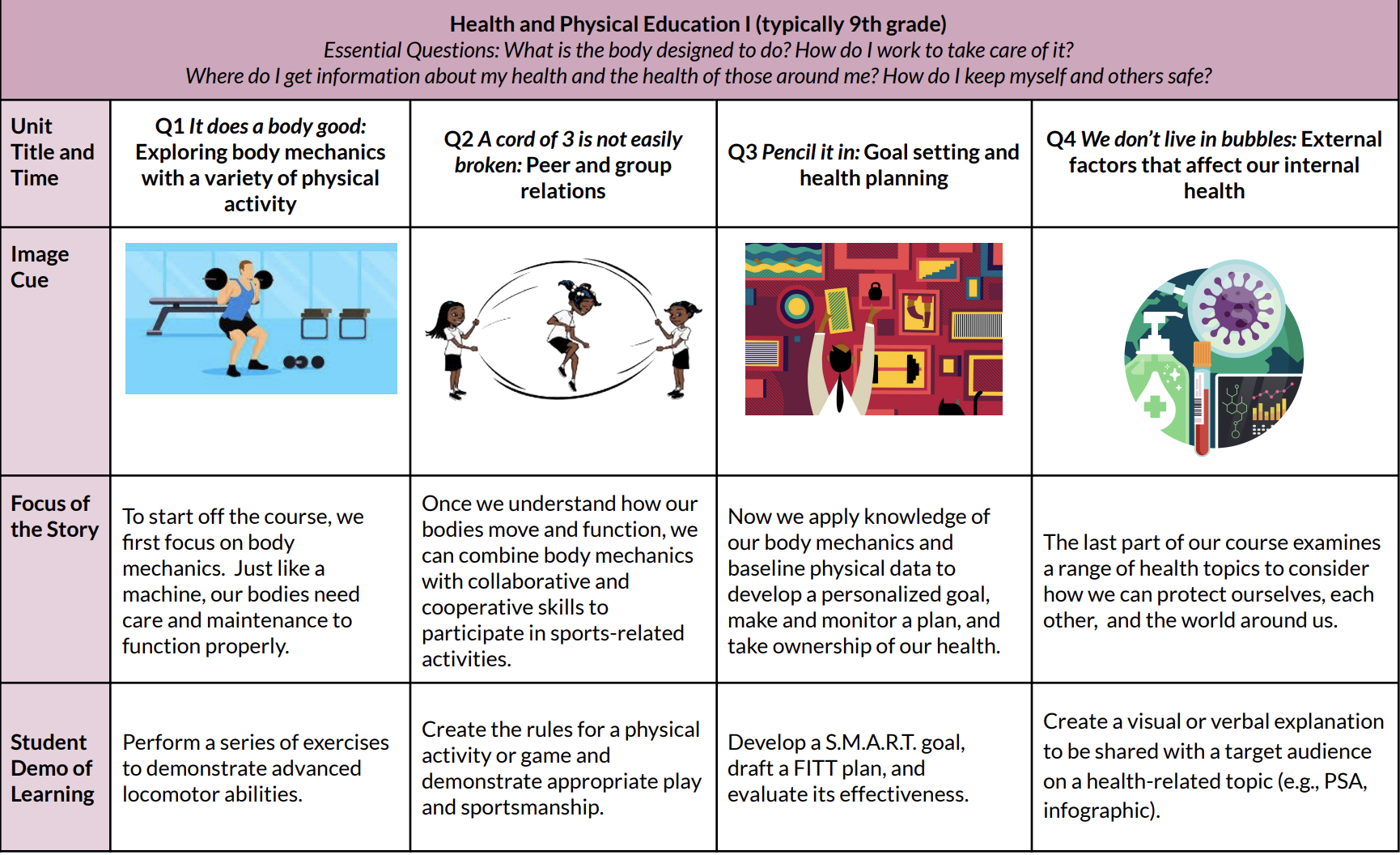

In recent years, Jacobs has further expounded on this idea of curriculum design as narrative writing with her book, with Allison Zmuda, called Streamlining the Curriculum. In this book, Jacobs and Zmuda advocate for the use of storyboards as a model for curriculum writing. They argue that the storyboard model helps condense curriculum down to its narrative essentials. Rather than unruly curriculum maps or vertical alignment documents, the storyboard model can provide a 1-2 page visual overview of a curriculum for a given course. Below are two curriculum storyboard examples taken from www.curriculumstoryboards.com, a website associated with Jacobs and Zmuda and their book.

Storyboard of a PE curriculum: https://curriculumstoryboards.com/resources/

Storyboard of a Biology curriculum: https://curriculumstoryboards.com/resources/

I agree that curriculum documents often need to be streamlined so that they capture the learning essentials in more stakeholder-friendly language (students and parents, for example). I also agree that too many complex curriculum mapping and vertical alignment projects result in unused, static documents. Curriculum documents need to provide a coherent framework, while still allowing room for creativity, evolution, and adaptation. I think the storyboard model can help teachers and schools to provide the necessary curriculum coherence in a format that can still be living and breathing in the hands of teachers and in the context of classrooms. However, what has really captured my interest about this storyboarding model is more the analogy of curriculum design as storytelling.

Storytelling as an Innately Human Trait

Storytelling is a phenomenon that is deeply tied to our humanness. Anthropologists point out that storytelling seems to be universal across cultures, and probably extends far back into human evolution. Some have suggested that storytelling has evolutionary adaptation value, serving a sort of “flight simulator” or “sandbox” role for real-world existence. Stories allow humans to imagine and share fraught scenarios with conflicts, lessons, and morals in order to “practice” our responses prior to facing similar scenarios in real life. Stories allow us to face challenges in abstraction and hone our ability to face the real world. In addition, the shared nature of storytelling allows humans to create shared meaning around experiences, both real and imagined; they help build social cohesion and culture.

Cognitive scientists point out that we are predisposed to appreciate the structure of story, as narrative models tend to align with how our brains process information and make meaning about the world. We cognitively seek out patterns, cause and effect relationships, and explanations for phenomena. We look for the intentions, motivations and agency of others. We seek out prototypical situations and archetypical characters. We have a theory of mind that allows us to imagine the feelings and intentions of others. We are cognitively inclined towards prediction, taking what we know and anticipating what will happen next. These elements make the structure of story uniquely compelling to the human mind.

Writing Curriculum as Story

In addition to streamlining curriculum, Jacobs argues that we can make curriculum more compelling to students when it's structured narratively, building on key components of the story format. When one considers the structure of story, units can become more than topics, skills, facts, and tests. Instead, they can capture and hold student attention, prompt deep thinking, and spur lasting memory, all while helping students develop and demonstrate the knowledge and skills outlined in curriculum standards.

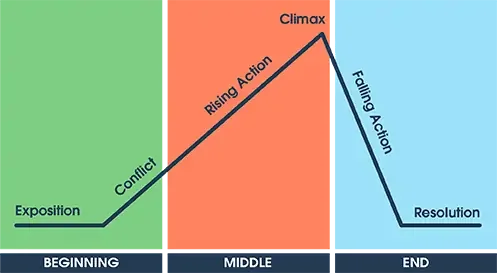

Somewhere in upper elementary or middle school, students in English Language Arts classes are often introduced to the narrative arc, such as the model displayed below. The arc is presented as a model of a typical story. A story involves a beginning, a middle and an end. In the beginning, a story requires the initial exposition, and the introduction of the story’s main conflict. Through the middle, a story is composed of various connected scenes of rising action that ramp up the tension, eventually reaching a climatic moment where the protagonist characters must overcome the conflict. After the climax, the tension diminishes quickly through scenes of falling action, finishing with the denouement that resolves final threads.

Image from Storyboard That, a digital storyboarding tool designed, in part, to support teachers with creative writing instruction.

Below I want to look at each of the components of the narrative arc one-by-one and draw out the analogy with curriculum writing, but before I do, I want to first loop back to Stranger Things.

Story Lines Within Story Lines

Like every good multi-season series, in addition to the narrative arc of each season, Stranger Things carries a larger storyline, one that transcends across the seasons, from the first scene of season 1 where we find the boys face-to-face with a demogorgon in the midst of their D&D quest, through, presumably, the series finale coming out next month. Furthermore, like any complex narrative, in Stranger Things, there are story lines within story lines. In addition to the overarching supernatural conflicts with the Upside Down, the characters face very natural conflicts, such as their friendships, bullies at school, parental divorce, growing up, personal identity, dating, and sexuality. Some of the characters have to face down their internal demons from past abusive relationships, personal loss, and trauma. There is also the historical backdrop of the Cold War conflict. Also like any good story, there are big themes in Stranger Things that transcend a single season– themes like loyalty in friendship (“friends don’t lie”), facing our repressed traumas (is the Upside Down a metaphor for our unconscious mind?), the identity versus role confusion of adolescence (a al. Erik Erikson), and the heroism of everyday people (I too was an ‘80s kid on a BMX bike saving the world… in my imagination).

As with a complex narrative, in curriculum writing there are story lines within story lines. Units, like the seasons of a TV series, can, for instance, string together within a larger course-long narrative arc, or, as another example, the vertical alignment of a whole middle school social studies curriculum could hang on several overarching themes.

The Narrative Elements of Writing a Curriculum Unit

While we could explore the narrative nature of curriculum writing on these more complex levels, so as not to overcomplicate the analogy, I’m going to proceed with a discussion of curriculum writing at the level of a single unit.

Exposition

The exposition of a story introduces the main characters and the setting, while also providing some important background information. The exposition should hook the audience to engage them in the story. There are often elements like foreshadowing or mystery used to draw in the audience to continue with the story. These should also be the elements at the outset of a good curriculum unit. The teacher needs to help the students connect the unit with their own prior knowledge and personal experience. To do this, the teacher needs to consider the setting and the characters– the classroom and the specific students in that classroom. The teacher needs to provide the necessary background information, while seeking to hook the students with a little mystery and some foreshadowing, prompting student anticipation of what is coming.

Conflict

Early in any story, the storyteller introduces the conflict, which creates tension in the story. The conflict drives the purpose of the story; it’s about overcoming the conflict and resolving the associated tension. There are many different types of conflict in literature: person versus nature, person versus another person, person versus the larger society, person versus herself, person versus his fate, person versus the supernatural, or person versus technology. As with the storyteller, a teacher needs to introduce a conflict near the outset of a unit. This conflict could come in the form of a problem or a challenge, which will give focus and purpose to the unit. Throughout, students will develop the knowledge and skills to address the problem; the unit will come to a climax when students are asked to demonstrate their learning to present a solution or demonstrate they can overcome the challenge. Another approach to unit conflict could come in the form of a question that students are not yet equipped to answer. With a question, the unit can then unfold as a series of lessons to help the students address the question. In order for the conflict element to compel students and generate the tension that captures and holds their attention, the problem, challenge or question should be relevant to them.

Often, the most relevant problems, challenges or questions for students are those that are real-world. When students can see that their learning is tied to a real-world situation, it helps to make that learning purposeful. However, an explicit real-world connection is not necessary. Stranger Things includes lots of other-worldly or supernatural elements, as do stories from the entire genres of fantasy and science-fiction; yet, many find these stories deeply engaging. Remember, the power of story is partly its ability to provide an imaginative abstraction of real world scenarios to serve as a creative rehearsal space. Units structured around imaginative conflicts can still capture student interest. At younger developmental levels, imaginative conflicts may even be best.

Rising Action

Once the storyteller introduces the conflict in a story, the tension slowly ratchets up through a sequence of subsequent scenes or episodes. This is the part of the story where the “plot thickens,” as they say. The storyteller develops the characters, while giving nuance and complexity to the conflict. The audience develops empathy with the characters, identifying personally with their struggle against the conflict. The storyteller keeps rolling out the plot, while maintaining enough mystery to keep the audience guessing and anticipating.

In a curriculum unit, the sequence of individual lessons drives the rising action. Each lesson pulls the students along, moving them towards the climatic point where they’ll be able to independently address the conflict. Each lesson addresses sub-questions, helps the students develop more knowledge, understandings and skills, gives the students opportunities to practice addressing elements of the problem, challenge or question, always maintaining the connecting thread of the storyline by referencing back to the overarching conflict. In addition, from lesson-to-lesson, a good unit should maintain a little mystery and provide some foreshadowing, leaving the students anticipating the next lesson.

The Climatic Turn

In a good story, the rising action continues to increase the tension until a climatic point where the conflict facing the characters comes fully to a head. At this point, the characters must risk it all in order to overcome the challenge, solve the problem, or defeat the enemy.

I would liken this to the culminating performance assessment of a unit. This is the point where the students have developed the necessary knowledge, understandings and skills. It’s when the time for practice is over. It’s time to face the conflict directly, without the teacher’s support. There are places within units for quizzes and tests, but it would be painfully anti-climatic for all of the unit’s rising action to culminate in a multiple-choice exam. Rather, the climatic performance moment in a unit should demand that students pull from all that they’ve learned during the unit to authentically answer the big question, present a solution for the problem, or demonstrate their ability to tackle the challenge. Ideally, this moment in the unit would require some sort of student performance or product. The student needs to create something, build something, demonstrate something, or present something. This demonstration of learning should align with the problem, challenge or question that drove the plot through the unit. Furthermore, if the unit conflict was rooted in the real-world, the culminating performance assessment should also have a real-world element.

Falling Action and Resolution

After the climatic turn in a narrative arc, the story usually wraps up quickly. What remains after the climax is for the storyteller to resolve the tension, to tidy up loose ends, and to emphasize key themes. Some refer to this as the “so what?” of the story. What was important about this story? Why should the audience care? What should they take away? In a curriculum unit, this is the place for feedback and reflection. The teacher can provide feedback to the students regarding the knowledge, understandings and skills they gained, the progress they made, and why the learning was important. Meanwhile, students can reflect on their own learning. How are they changed at the end of this unit? What are the takeaways that will stay with them?

From Static Curriculum to Immersive Stories

Too often curriculum entails a set of dry standards, a list of disjointed topics, or a sequence of disconnected activities. Jacobs and Zmuda note that most curriculum is written in a “tone [that] is typically officious and often burdensome.” They describe curriculum documents as “teacher- and system-centric”; curriculum often says to students, “these are the content, standards, and proficiencies we will cover while you sit in the room with your teacher.” Of course, curriculum must address the mandated standards, but the standards are not the curriculum. The curriculum is how the teacher chooses to address those standards. Why not engage students in learning the standards through story? Why not adopt the characteristics of narrative that have compelled humans across cultures for millennia? Why not build elements into units that hook students, capture their attention, provide foreshadowing, generate mystery, leave them anticipating what’s next, ratchet up the tension, and impel them to face a conflict face-on? When curriculum is written as stories, according to Jacobs and Zmuda, “each student sees the curriculum ‘is for me– my teacher is inviting me to join this journey.’”

Another word for a journey? A quest! What if we approached curriculum units a little more like an epic quest in the role-playing D & D game? Role-playing games are compelling because they invite the players in as characters in the story. When a teacher creates a narrative-driven curriculum unit, the students aren’t a passive audience for the story; rather, the students are the characters, and the classroom is the setting. It’s as if the teacher is the Game Master facilitating the narrative, but inviting each of the students to play their own character, forming together as a party, seeking to overcome the conflict of the quest and achieve the quest objective.

References

Jacobs, H. H. and Zmuda, A. (2023). Storyboarding your curriculum. Educational Leadership, 80(5), ASCD.

Toddle. (2023, June 28). Moving from curriculum maps to curriculum storyboards (No. 08) [Broadcast]. https://slp.toddleapp.com/episodes/strategic-curriculum-planning-heidi-hayes-jacobs/