A Model of Service-Learning in IB Business Management

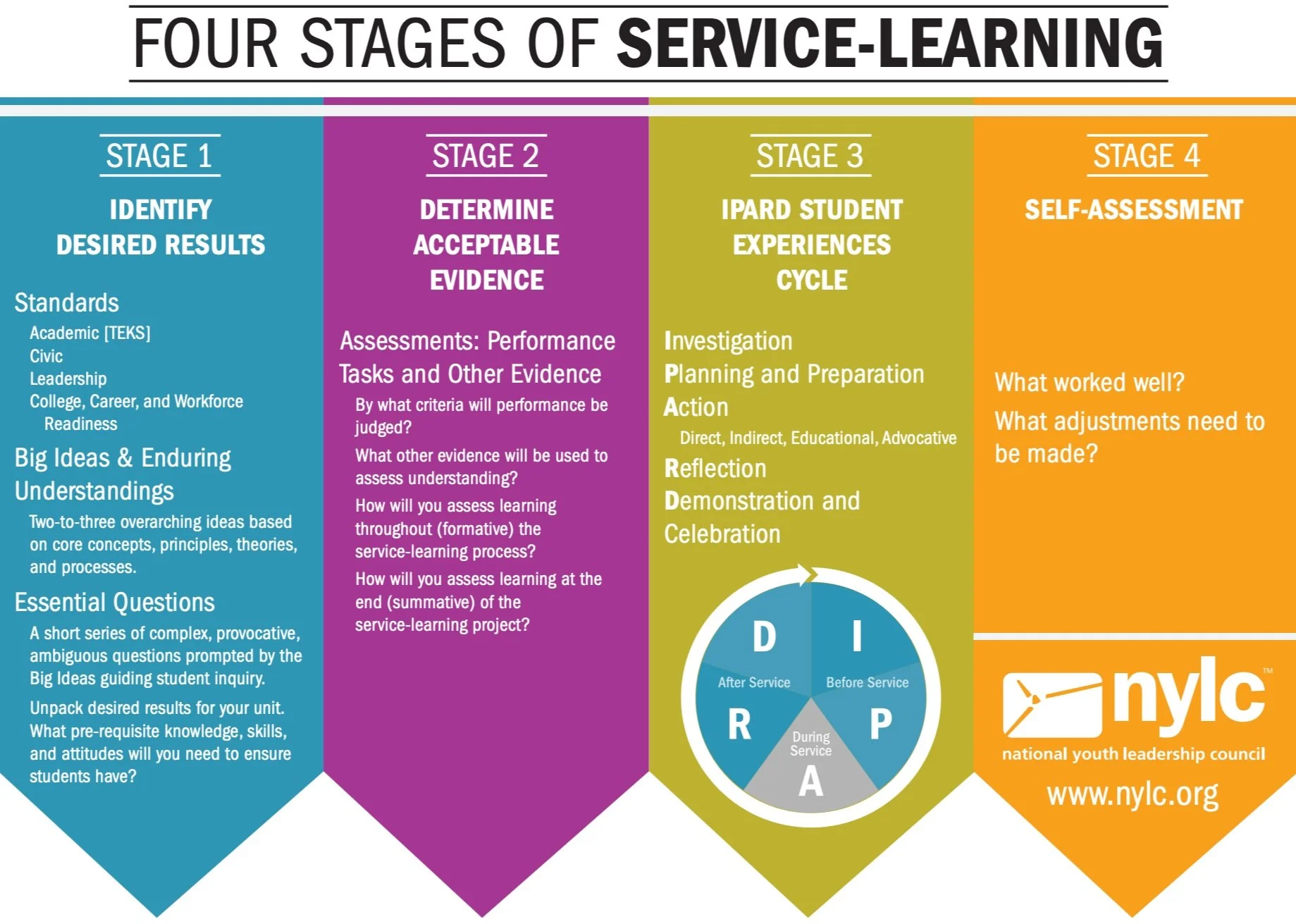

Image from the National Youth Leadership Council (www.nylc.org). I highly recommend NYLC’s resources on service-learning K-12 schools, including their K-12 Service-Learning Standards (https://nylc.org/k-12-standards/).

This post is targeted primarily at an audience that is already familiar with the International Baccalaureate Diploma Program (IBDP). For those not familiar with the IBDP, in short, it’s an internationally recognized high school diploma program, developed by the International Baccalaureate Organization (IBO). Students who participate in the IBDP do so in their final two years of high school. Students take six different courses, each of which spans the two full years of the program. In addition, students must complete 3 different “core” requirements which include a Theory of Knowledge (TOK) course, the completion of a 4000 word research paper called the Extended Essay, and CAS, which stands for Creativity, Action and Service and stipulates certain requirements for extra-curricular involvement.

While I’ve taught a number of IBDP-level courses for a number of years (IB History, IB Business Management and TOK), I am not an expert in the program, nor an expert in the CAS component of the program. From my understanding, student service experiences for CAS do not need to involve “service learning,” though the IBO does encourage a service learning approach, and I think there are hints that this encouragement will become stronger in the future.

As per the IBO’s teacher support materials for CAS, Service is defined as: “collaborative and reciprocal community engagement in response to an authentic need.” The document then goes on to say, “By investigating and identifying a community need, then determining a plan of action that respects the rights, dignity and autonomy of all involved... you are performing service.” Within these IBO teacher support materials there is a section called “Integration of service learning with the DP subject groups,” which states, “One aspect of service learning is that engagement in service evolves from being exposed to and developing an understanding of issues and subject matter studied in the academic curriculum.” The IBDP CAS Guide encourages service learning as part of the service component of the CAS requirements (pgs. 20-22). It lists five stages of Service Learning: Investigation, Preparation, Action, Reflection and Demonstration.

The below described model is from my perspective as a IBDP subject area teacher, specifically an IB Business Management teacher. The CAS program has specific requirements for student reflection and a student-initiated CAS project. That is not my area of expertise and my example below does not specifically address those requirements. However, I believe this is a potential model, in the spirit of IBO-encouraged service learning, from the subject area classroom side of the service learning relationship with CAS. Furthermore, as I touch on below, I believe this model is about more than meeting an IBO requirement; rather, I think this about improving teaching and learning more generally within the IB subject area classroom.

Service Learning

Service Learning is different from the more traditional definitions one tends to think of with the term “service.” These definitions refer to service in the sense of "community service." Service in this sense is about “volunteerism;” it’s about giving some of your time in a volunteer capacity to help in some way in the community. There is real value in this form of service, but “service learning” is something different; it involves not just giving of one’s time, but rather, it is also epistemological. The concept of service learning is rooted in a philosophy of how humans learn and come to know the world. It’s rooted in a constructivist theory of knowledge, meaning that humans come to know -- they learn -- by engaging the world and constructing knowledge while doing that. Service learning, then, happens in the interplay between action and reflection. It’s about reflecting on a situation in the world, acting in the world by engaging that situation, then stepping back and reflecting again on the situation as well as one’s action upon it. In this way, one constructs one’s own knowledge of the world, and his or her ability to have an impact on the world. So service-learning -- or action-reflection -- is not just about using one’s learning to contribute to the world, but rather is actually about learning the world while contributing to it.

Implied in the five stages outlined in the IBDP CAS Guide is that the stages are linear, but, ideally, service learning should be illustrated as an action-reflection loop. A student engages in investigation in order to then prepare and implement action in the world, which is followed by reflection, which sets the stage for further investigation to prepare and implement further action, etc. When articulated in this way, service learning should not just be a thing done in school; rather, it should be intrinsically the way that one learns in school. Because of the traditional meaning of service as “volunteerism,” the concept of service learning is often misunderstood. It should be less about learning while engaging in one-off volunteer activities, and more about authentically engaging the world while learning. Of course, the term “service” is apt here, given that this engagement in the world needs to contribute positively, but it goes beyond that.

History of the ICS Entrepreneurship Workshop

I’ve been the faculty supervisor for an extra curricular student service club at my school since 2015. My school is the International Community School of Addis Ababa, in Ethiopia. The club was started by some students who wanted to partner with a specific project called the CCC Children’s Home. The CCC Children’s Home is a resident care-home for about 60 children ages 3 - 20 in Wolaita Soddo, a town located in southern Ethiopia, about a 6 hour drive from Addis Ababa. The project also supports an additional 15 young people who grew up at the home, are now in their early twenties, and are in a semi-independent transition program. The CCC Children’s Home is intended to be a last-resort care option for those without parental or other family or community care options. In the parlance of those working in this field, the CCC Children’s Home cares for OVCs, or “orphans and vulnerable children.” The home was started and is managed by an Ethiopian charity called Children’s Cross Connection (CCC). In the paragraphs that follow, I will refer to my school as “ICS,” and this student service club at ICS as “the service club.” I will refer to the CCC Children’s Home project simply as “the CCC Home.”

In the summer of 2016, five young adults, three boys and two girls, all of whom had grown up at the CCC Home, graduated from their respective post-secondary programs. It was an exciting summer for the CCC Home as it was the largest group of graduates they’d had to date and everyone had high hopes for their futures. Unfortunately, it wasn’t long before it became clear that finding employment wasn’t going to be easy. There is a growing challenge in Ethiopia of youth unemployment, including rising unemployment rates even for those with post-secondary education.

A year after graduating, none of these five young adults had prospects of employment to support themselves. The Service Club decided to investigate this issue and how we could support these young adults. With suggestions from the CCC Home, we landed on the idea of a workshop to help these young adults develop proposals for small businesses by which they could support themselves. ICS was uniquely positioned to host an Entrepreneurship Workshop. It had the facilities, it had the connections to the Addis Ababa business community and there was an IB Business Management course being taught in the high school for the first time. The Service Club started making preparations to host a weekend-long workshop on the ICS campus, not only for these five young adults, but also for other older kids from the CCC Home. The goal was to not only help the five develop business proposals immediately, but to also plant the ideas of entrepreneurship for the kids not yet at the same life-stage, with the hope that they may consider entrepreneurship as a means of future livelihood as well.

Part of the genius of this idea was that it could bring together the planning and organizing efforts of the Service Club with the business knowledge from the IB Business Management classes. The club could deal with the organizing and logistics of hosting the event, while the Business classes could lead the workshop sessions on various topics. We hosted the first Entrepreneurship Workshop in March, 2018. Nineteen high school and post-high school young people from the CCC Home attended the workshop. The club did fundraising to cover the transportation, housing and food for the attendees, and curated a workshop program that included sessions on different business topics led by the IB Business students, interspersed with guest speaker sessions with entrepreneurs connected to our ICS community.

After the success of the first workshop we decided to make the Entrepreneurship Workshop an annual event. It became clear that if entrepreneurship was to be one possible route to financial self-sufficiency for some of the young people at the CCC Home, it would take more than a one-time weekend event to promote these ideas. We also heard from other OVC organizations that their kids could also benefit from this initiative. The Entrepreneurship Workshop in March 2019 expanded to 40 attendees, 30 of which came from the CCC Home and another 10 from the Sele Enat orphanage in Addis. Then in March 2020, the workshop expanded still further to 60 attendees, 40 from the CCC Home and the rest from the Sele Enat orphanage, A-Hope for Children and Selamta Children’s Project, all organizations working with OVC populations. For the fourth iteration of the workshop, due to Covid restrictions, the IB Business students, together with the Service Club compiled a virtual workshop via a Google Site that included video-recorded sessions, various downloadable practice exercises, and several video-recorded interviews with Addis-based entrepreneurs.

The Challenge of Youth Unemployment in Ethiopia

The Unemployment Rate is a key metric of macroeconomics in any country, but it is notoriously difficult to measure. The common formula used to calculate the Unemployment Rate is: [(Unemployed / Total Labor Force) x 100]. It’s not uncommon to find different numbers for the Unemployment Rate for the same country and for the same period. This is partly because the term “Unemployed” is defined differently depending on who is doing the measuring. Typically, for a person to be classified as “Unemployed” requires that they meet three criteria: a) currently without work, b) currently available to work and c) currently seeking work. This omits workers who have given up on looking, have temporarily stopped looking, or never bothered to start looking. It also doesn’t consider people who are marginally employed or underemployed.

Despite the data limitations, one can still get some sense of the problem in Ethiopia by looking at the statistics available. According to the Ethiopian government’s Central Statistical Agency (CSA), the National Unemployment rate in 2018 was 19.1%, which was up from 16.9% in 2016 (cited in “Ethiopia Unemployment Rate”). This same CSA report pegged the nationwide Youth (ages 15 - 29) Unemployment Rate at 25.3% (Tamrat). A USAID report in July 2017 estimated the Youth Unemployment Rate in Ethiopia to be as high as 27% (“USAID Fact Sheet”). An International Labour Organization (ILO) press release from 2016 pointed to part of the youth employment challenge. It stated that 73% of Ethiopia’s population is under the age of 30 and that 3 million young people in Ethiopia enter the labor force annually (“ILO to pilot”).

Mission of the Entrepreneurship Workshop

The mission of the Entrepreneurship Workshop draws on the work of Muhammed Yunus, Nobel Peace Prize winner and founder of Grameen Bank in Bangladesh. Yunus’ concept of “Social Business” has informed the Workshop. It is also important in the IB Business course curriculum as developed by myself and the other business teacher at ICS. In his book, Building Social Business, Yunus points out some important weaknesses in the traditional charity / non-profit model of addressing poverty. While charity work is driven by a social mission, out of necessity, charities are forced to invest large amounts of time and resources in fundraising in order to sustain their work. These self-sustaining activities distract from the effectiveness of these organizations to address their mission. Furthermore, many of the poverty relief efforts of charities and nonprofits are just that -- relief efforts; they are often unable to address the underlying causes of poverty, and can even contribute to a state of dependency. On the other hand, though Yunus is a pro-business economist, he has also developed a critique of, what he calls, traditional profit-seeking businesses. He argues that while these organizations are very good at generating profits for the sake of the owners, investors and shareholders, they’re not good at addressing social needs. In fact, too often traditional profit-seeking businesses exacerbate social issues because of the exploitative nature of their profit-seeking motive. Yunus does not believe that all charities or traditional businesses are bad; he believes there is a place for each, but he also argues that there can be a third way. Yunus believes that entrepreneurship can improve and empower the lives of the poor. He has a name for businesses that are started and run by people in poverty for the sake of improving their own lives; he calls them Type 2 Social Businesses. Yunus also believes that a new sort of business can be established that intentionally chooses to surrender the traditional profit motive to a higher social mission; he calls these Type 1 Social Businesses.

The mission of the Entrepreneurship Workshop is to help Ethiopian young adults, particularly those within the OVC context, establish, as Yunus would call them, Type 2 Social Businesses. These are businesses that empower people in poverty to take control of their situation, and improve their lives and those of their families. It’s in the context of these Type 2 Social Businesses that Yunus says that people should be able to “wake up in the morning and say, ‘I am not a job seeker, I am a job creator’” (Elizabeth). Small business entrepreneurship is not a silver-bullet solution to the problem of high youth unemployment in Ethiopia, but for those with the initiative and ingenuity, it is a potential means to greater financial self-sufficiency. Instead of searching for jobs that don’t exist, the job-seeker can become his or her own job-creator. The aim of the annual Entrepreneurship Workshop is for attendees to walk away with, at least, a new inclination to consider entrepreneurship; better, we hope they walk away with ideas, knowledge, tools and inspiration that could empower them to start their own small businesses either now or in the future.

Model of Service Learning

Admittedly, the Entrepreneurship Workshop is not a perfected model of service learning, but, through refining over the past few years, many of the components are in place upon which to further build. Service learning happens on two levels with the Entrepreneurship Workshop. One level happens within the Service Club, a club in which many IBDP students participate as a CAS experience. The club engaged in a period of investigation of the problem of unemployment -- and the club returns to this investigation each year -- and developed the idea of the Entrepreneurship Workshop as an action response to that investigation. The club spends many weeks in the preparation stage, breaking into different committees to arrange the logistics of hosting the event. The weekend-long workshop itself is the action stage. The club then follows up with a number of meetings dedicated to reflection, which involve strategies for follow up, as well as documenting ideas for improvement the following year. From these post-Workshop reflections, the Service Club has initiated several follow up actions. These include providing funds for a handful of high school residents of the CCC Home to start temporary small businesses during their summer school-break in order to experiment with ideas and gain some first-hand business experience.

On a second level, the Entrepreneurship Workshop has become integral within the curriculum of the IB Business course at ICS. This starts from the opening lessons of the course in Year 1, where students are introduced to business in the context of social issues in our host country of Ethiopia, including issues of poverty and unemployment. Students learn that this course is not just to help them pursue their own future careers, or help them become rich; rather, at the heart of the course is the slogan of B Corp of “Using Business as a Force for Good” (“About B Corp”). Students learn of Mohammed Yunus and his concept of Social Business while reading and discussing parts of Yunus’ book, Building Social Business. This is not to say that the whole course focuses only on Yunus’ model of Social Business, but it sets a tone, one that is returned to throughout the course, that business is a human enterprise of applying innovative solutions to solving social problems and addressing human needs; that rather than being selfish and exploitative, business enterprises should produce social and environmental benefits.

Investigation of this theme of “business as a force for good” continues throughout the course, but students move into preparation and action in the 2nd semester of Year 1 when they sign up to lead a workshop session on a specific topic for the Entrepreneurship Workshop. Students must distill a topic to its most essential elements and find ways to make that topic applicable in the local Ethiopian context; this becomes a major summative demonstration of learning. These student-led workshop sessions are one hour long each, so they’re more than just presenting a slideshow presentation at the front of the room. These sessions require students to interact with the workshop attendees, to develop practice activities that are relevant, and to sit and work with the attendees while they apply what they’ve learned to their own business ideas. Throughout the weekend of workshop sessions, the IB Business students must consider the ideas of Mohammed Yunus in a real-world context. What are the challenges faced by these young people when it comes to developing a business plan, getting access to start-up finance, and working through bureaucratic red-tape? What promotional methods can work, how can one develop a product USP, how can one scale up a small business to achieve economies of scale? How can one conduct market research to identify gaps in the market and current needs that are not being fulfilled? How can one develop a product idea that will meet a current need, and then secure the necessary inputs to produce and market that product? All of these business questions become real to the students when they’re pondering them together with a real person whose life can immensely benefit as he or she figures out answers to those questions.

The back and forth interplay between reflection and action around the Entrepreneurship Workshop is now well established in the IB Business course. Students investigate the problem of youth unemployment within Ethiopia and how the concept of Type 2 Social Businesses and small business entrepreneurship can empower young people and improve their livelihoods. Students devote class time to preparing for their workshop presentations and activities in the lead up to the workshop event. Students engage in action by leading their workshop session and participating in discussions with the attendees. Their engagement with the attendees during the workshop then becomes the basis for further reflection back in the classroom. We are able to apply future learning to the real-world challenges and ideas that arose from attendees during the workshop, and even follow up directly with some of those attendees. This is not perfectly developed yet; the post-workshop components are definitely an area for further growth. How can the class further reflect on the action of the workshop, and how can that lead to further follow-up action? There are real time restraints within the IB Business curriculum, but with what is already in place, it wouldn’t take much to build on the model already developed and strengthen it.

Brief Description of the Entrepreneurship Workshop

Since the first Entrepreneurship Workshop in March 2018, we have attempted to create differentiated tracks of workshop sessions. This is due to many returning attendees each year and the need for these returnees to expand upon and deepen their knowledge. The most recent Workshops have involved three different tracks. Level 1 is for new attendees or those not yet thinking seriously about their future livelihoods. The Level 2 track is for those who have attended during previous years; these sessions provide opportunities to go deeper or to explore new topics. The Level 3 track is intended for those who are very serious about starting their own business, or maybe already have. Each workshop session is one hour in length and involves the IB Business students presenting some information on the topic, followed by real-world examples and opportunities for practice, as well as opportunities to apply the knowledge to an actual business idea. The IB Business students not only present, but also sit and work with the attendees to discuss their ideas and provide suggestions on how to apply what they’ve learned in the session. Each track is given a hypothetical but real-world business idea to use for practice and application, though if attendees have their own ideas, they are welcome to apply their learning to it.

We have interspersed guest speaker plenary sessions throughout the schedule, usually bringing in three or four guest speakers over the course of the weekend-long workshop. The selection of these guests is done with an attempt to balance recognizable, big-name business people that have the ability to inspire, with recent, small-business entrepreneurs who have very practical and relevant experience with the challenges of starting a business. Each year since the first, we’ve tried to assemble a panel Q & A session with past attendees who have since started their own businesses. These past attendee-turned-entrepreneurs have been able to speak directly to the steps, challenges and rewards of their experience with entrepreneurship.

Impact of the Entrepreneurship Workshop

Measuring the impacts of service learning is a challenge and I’ll admit that we do not have proper quantitative data on its impact. What we do know is that at least six past attendees of the Entrepreneurship Workshop have gone on to start their own small businesses. We know that five of those are still in operation and still providing a source of income for the entrepreneurs who started them. We also have witnessed a culture shift among the teens at the CCC Home. Many of them now speak of entrepreneurship as a viable option for their futures. Many of the high-school aged residents at the home have experimented with some small business enterprises during their school breaks. Much like with the proverbial “lemonade stand” in a North American context, these high schoolers have gained experience and skills while selling mobile phone recharge cards, used clothing, coffee and tea, charcoal, mobile phone accessories, etc. During the long interruption to school due to the Covid pandemic in 2020, a group of these high schoolers initiated a small poultry and egg business together. They bought and raised some chickens, and are now able to sell the eggs laid daily.

We also know from the growth in attendees each year and the feedback we get from them that they feel that we’ve hit upon a real need. Of course, youth unemployment is a knotty problem, and we cannot claim at all to have solved it, but we’ve witnessed the eager participation of the attendees for whom it’s a real personal challenge and who recognize the usefulness of what we’re providing.

In light of the epistemological purpose of the Entrepreneurship Workshop as service learning, perhaps it's most important to point out that the IB Business Management course at ICS continues to grow in popularity among our students, and, as the teachers of the course, we continue to hear from students, both past and present, that engagement in the workshop and the action-reflection centered around it, is one of the more valuable learning opportunities of their IBDP experience.

Works Cited

“About B Corp.” Certified B Corporation. Web. Accessed April 19, 2019.

“Creativity, action, service teacher support material.” IB Publishing. International Baccalaureate Organization. Web. Accessed May 7, 2021.

“Diploma Programme Creativity, Action and Service Guide.” International Baccalaureate Organization. Geneva, 2015. Web. Accessed April 21, 2021.

Elizabeth, Shilpa. “Youngsters are job seekers not job creators.” Economic Times. India Times. Sept 2, 2015. Web. Accessed April 19, 2021.

“Ethiopia Unemployment Rate.” Trading Economics. Tradingeconomics.com. Web. Accessed April 19, 2021.

“ILO to pilot a youth employment services centre in Ethiopia.” International Labour Organization. Press Release, March 6, 2018. Web. Accessed April 19, 2021.

Tamrat, Wondwosen. “Job creation plan -- What role for higher education?” University World News: Africa Edition. September 21, 2019. Web. Accessed April 19, 2021.

“USAID Fact Sheet - Developing Ethiopia’s Youth.” USAID - Ethiopia. July 2017. Web. Accessed April 19, 2021.

Yunus, Mohammed. Building Social Business. PublicAffairs. New York, 2010. Print.