Will LLM Generative AIs spell the end of the humanities? Would that be a problem?

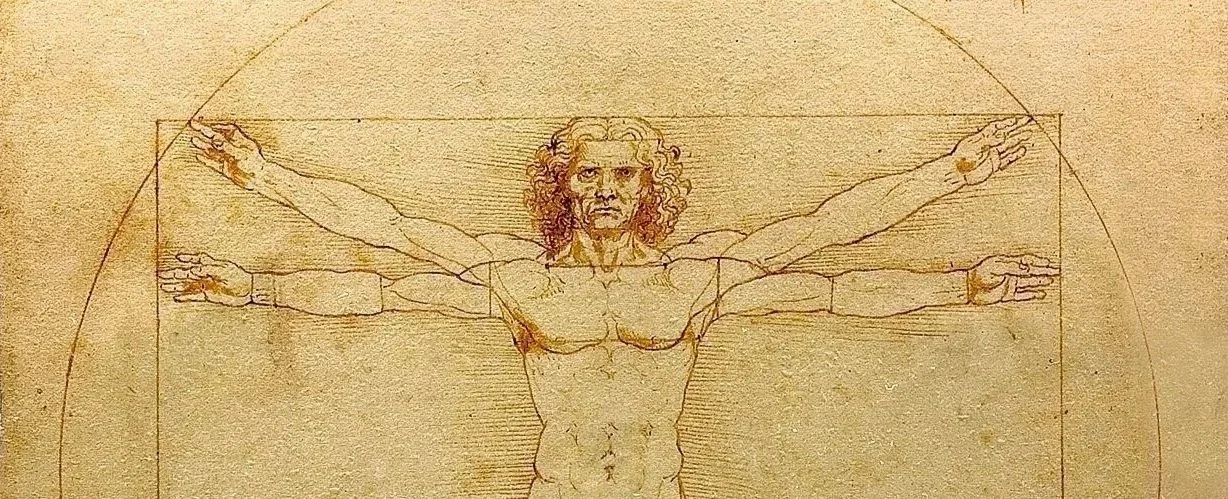

Image of Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man (Public Domain: Luc Viatour / https://Lucnix.be)

Some trends in the humanities have been bad for a while. Based on university student enrollment in humanities degrees, the trend has been a steady decline for the past several decades. Some point to the rising cost of a university education as a culprit; students choose degrees that offer not just debt, but gainful employment after university. Despite these trends, in many universities, because they’re considered important to a well-rounded undergraduate education, even engineering and computer science majors are required to take some humanities courses.

Stepping down to the secondary school level, the influence of the humanities remains relatively strong because of the belief that secondary school should provide students with a broad education that prepares them for personal and civic life, not just for future employment. At the secondary level, students are often required to study additional languages, history, and language arts, including literature and grammar.

Origins of the Humanities

Though disciplines like history, literature, and philosophy extend far back into human history, the category of the humanities arose out of the European Renaissance. Renaissance humanism emphasized human dignity and potential; the humanities of that period involved the study of Latin, grammar, classical literature, poetry, history, rhetoric, and philosophy. Each of these subjects shared an emphasis on written texts. Renaissance humanism was, in part, a movement that sought to recover the literature and philosophy of classical antiquity. The written word was both the object of study and its means.

The Humanities: Literacy as Epistemology

This emphasis on written text remains a unifying feature of the subjects of the humanities today. This is not to say that reading and writing are not important in other disciplines. Scientists, for example, certainly must be literate; but written texts are more of a means to an end in those fields. In the humanities, reading and writing are epistemological; texts are the data, textual interpretation is the method, and the act of writing is the meaning-making process. To study history requires reading both primary texts and the narrative interpretations of historians. The study of literature involves interpreting meaning from poetry and prose. Studying philosophy requires the student to make sense of the written treatises of philosophers. To be a historian, a novelist, a poet, or a philosopher requires that one write, write, and write some more, not just to share knowledge, but to create it. It’s no coincidence that the humanities grew in influence during a period of expanding literacy rates, the invention of the printing press, and the wider distribution of texts.

There’s a degree to which the study of the humanities is important for general knowledge, but the real value of the humanities, the real import of engaging deeply with the written word, is the way in which it develops our ability to think– reasoned thinking, critical thinking, moral thinking, aesthetic thinking, creative thinking. It’s about learning to question social assumptions and political powers, supporting claims with evidence and reasoning, developing empathy and advanced theory of mind capacities, imagining and creating beauty, and wrestling with moral quandaries.

The Humanities as Cognitive Development

Neuropsychologist Donald Hebb coined the phrase: “neurons that fire together, wire together.” This phrase explains the neurological basis for human learning. Through repetition, neural pathways are strengthened, making it easier to access those pathways and build on them in the future. One learns to play a musical instrument through repetition so that the firing of those neural pathways becomes almost automatic. The same is true for other cognitive processes including our ability to think reasonably, critically, morally, aesthetically and creatively. These cognitive capacities are strengthened when we study the humanities, which has always required deep, sustained, effortful immersion in texts.

Will Generative AI Lead to Diminished Human Literacy and Thinking?

Generative AI is not the first technology to alter human literacy. We’re seeing changed literacy habits in students who grew up with mobile phones, video-streaming screens, and social media. Professors report that students now arrive at university having read very few full novels; instructors bemoan the complaints they receive when they assign longer readings. Though this trend is not new, I fear that the Generative AI tools of the last few years, built on Large Language Model AIs, could radically accelerate these trends. Because these AI systems are trained on human language, these systems have the capacity to engage with the written word for us. Until recently, our interaction with generative AI has mostly involved a text-chat platform. Users have been required to prompt the AI in writing and then read its response. That model is rapidly changing; ChatGPT 5.1, the version available currently with a paid subscription, has an advanced voice mode where one can speak prompts and the AI will “speak” back as if in a natural conversation.

What will happen if humans off-load reading and writing to Generative AI? The content of the humanities, the substantive knowledge, probably won’t be lost, but if our engagement with that knowledge is through conversations with AI, rather than through the effortful work of reading and writing, we will lose the syntactic knowledge of the humanities. If we stop reading and writing, how will this alter our neurological wiring? How will this impact our cognitive capacities for critique, creativity, empathy, imagination, aesthetic appreciation, logical and moral reasoning, and meaning-making? I’m concerned that, if we off-load human literacy to generative AI, the consequences could be dire not just for the humanities, but for humanity.

Maybe Schools Need to Double-Down on the Human

Generative AI has spurred a lot of existential hand-wringing in education circles. Part of the debate has focused on the type of schooling we need to prepare students for the future. The effort to predict what students will need in the future has always been a fool's errand; it’s become that much more so given the accelerated pace of AI development. That being said, let me propose my own idea for schools for the future. What if schools, instead of chasing technology-driven “innovation,” double-down on the human? What if schools re-commit to the learning value of studying the humanities, not only for its content, but for the epistemological value of reading and writing? I’m not advocating for fully tech-free schools; I’m also not saying that schools shouldn’t be working with AI. But maybe there should still be some spaces within schools, where old-school reading and writing is the priority. Maybe there should be less technology, rather than more in those spaces. Maybe students should hold printed and bound books in their hands, and do more writing, sometimes with pen to paper, in those spaces. Maybe the emphasis in those spaces should be on literacy, not as a means to an end, but as the cognitive practice of human thinking. Maybe we’ll even discover in the future, as AI tools proliferate, that these uniquely human thinking capacities – critical, creative, moral, reasoned, aesthetic – honed through reading and writing, are actually in high demand.

References

American Academy of Arts and Sciences (2015). The state of Humanities: Higher education 2015. Humanities Indicators. https://www.amacad.org/publication/state-humanities-higher-education-2015

D’haen, T. (2011). The Humanities under siege? Diogenes, 58(1–2), 136–146.

Hebb, D. O. (1949). The organization of behavior: A neuropsychological theory. John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Hughes, A. (2025). As arts and humanities enrolment declines, could making programs more practical help? The Current. CBC Radio. https://www.cbc.ca/radio/thecurrent/arts-and-humanities-practical-1.7469940

Lurye, S. (2024). Not-so-great expectations: Students are reading fewer books in English class. Associated Press: https://www.ap.org/news-highlights/spotlights/2024/not-so-great-expectations-students-are-reading-fewer-books-in-english-class/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

McMurtrie, B (2024). Is this the end of reading? The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/is-this-the-end-of-reading?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Robert, G. (2021). The Humanities in modern Britain: Challenges and opportunities. Higher Education Policy Institution, report 141. https://www.hepi.ac.uk/reports/the-humanities-in-modern-britain-challenges-and-opportunities/

Swan, L. S. (2024). The end of reading: Why aren’t college students reading–and what can we do about it? Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/college-confidential/202405/the-end-of-reading?utm_source=chatgpt.com