Content Representations (CoRes) as a Tool for Pedagogical Reasoning

Cover image of book by Loughran, Berry & Mulhall (2012) where they detail their work on Content Representations for the teaching of science (and another tool that they called PaP-eRs).

Lee Shulman, PCK, and Pedagogical Reasoning

During his AERA address in 1985, Lee Shulman coined the term, Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK). He used this term for the knowledge domain that is unique to teachers. He argued that subject-matter content knowledge and pedagogical knowledge were both necessary knowledge domains for teachers, but neither were sufficient for effective teaching. Shulman argued that teaching requires PCK, which emerges from the amalgamation of content knowledge and pedagogical knowledge, together with the teacher’s knowledge of the students in the room, through the act of teaching. According to Shulman, it’s PCK that empowers teachers to pedagogically transform subject-matter into forms that guide the specific students in the room to understanding.

For Shulman, teaching is never just a transmission of knowledge from teacher to students. It also requires more than following standardized pedagogical procedures. Shulman argued that teaching is a cognitive act; teachers have to draw on their knowledge of the subject-matter, their knowledge of pedagogical methods, and their knowledge of the students, and then create examples, metaphors, explanations, illustrations, models, practice exercises, etc. that will make the subject-matter comprehensible to the students. Shulman referred to this cognitive and creative work as “pedagogical reasoning” (I said more about this previously when I wrote about the role of teachers as “explainers”).

Content Representations (CoRes)

Working in the context of teacher training, Loughran et al. (2004) wanted to develop a tool that would help pre-service teachers develop the practice of pedagogical reasoning. They hypothesized that a tool that would force teachers to engage in pedagogical reasoning would facilitate both the enactment of teacher PCK and the development of it. Loughran et al. (2004) created a tool that they referred to as “Content Representations,” which they named “CoRes” for short. CoRes has since been used by other researchers as a tool for both measuring PCK, and for developing it, both in pre-service and in-service teachers.

I’m currently conducting some case study research with several secondary teachers, exploring the value of a particular model for developing teacher PCK. I’m using the CoRes tool as part of the model. In an effort to gain more experience with the tool myself, I recently worked through it with a common topic of a high school introductory economics course. It’s worth noting upfront that, though I’ve ended up teaching economics, I studied very little economics in university. Therefore, if I have any readers who are true economists, I hope you’ll forgive any spots in my example that betray my lack of academic economics background.

Before diving into the example, I also want to note that the CoRes tool is not meant to be a lesson planning tool. It does not necessarily contain all of the elements one would need to pick-up and teach this topic tomorrow. Rather, it’s meant to be a pedagogical reasoning tool, meaning that it’s intended to force the teacher to do the cognitive work necessary to transform the subject matter for the purpose of student learning. I’ll also point out that I decided to go in-depth with my use of the tool. Any reader who is also a teacher will look at this and think, “There’s no way I have the time to work through this process for each topic I teach.” To that I would absolutely agree, and I’ll provide two responses. First, there is value in the use of the tool at a less in-depth level; it’s absolutely something you can work through quickly on a first go-around, and then return and add to it in the future when you teach the same topic again. In that way, it can become a tool that reflects your thinking about teaching a topic as it develops over time. Secondly, I think the tool can promote a habit of thinking that then doesn’t require use of actual document for every topic. By using the CoRes tool for a few important topics within your subject-area, and then returning to it periodically for other troublesome topics, it can help you refine your practice of pedagogical reasoning, a practice that will then become more naturally ingrained in your teaching.

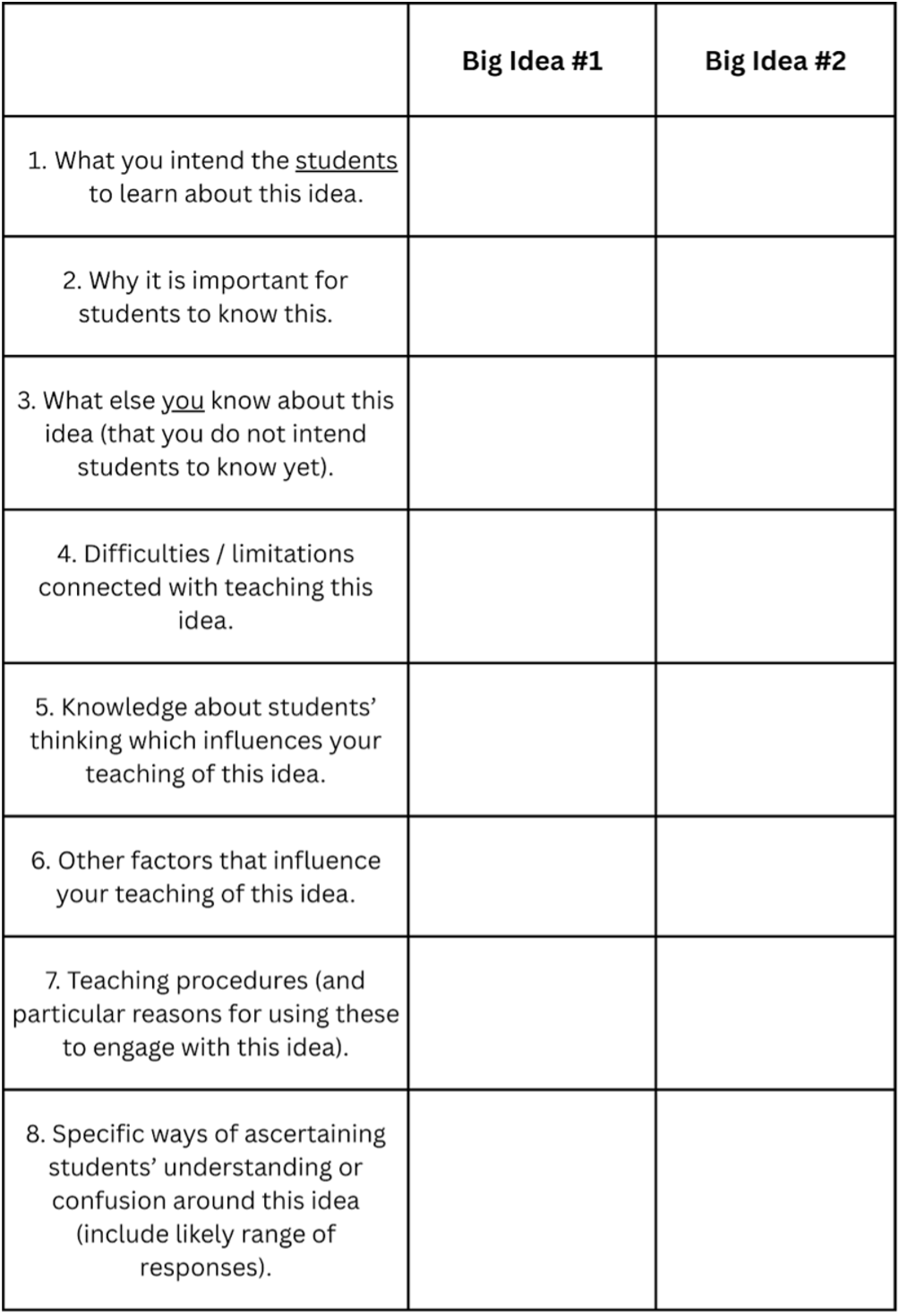

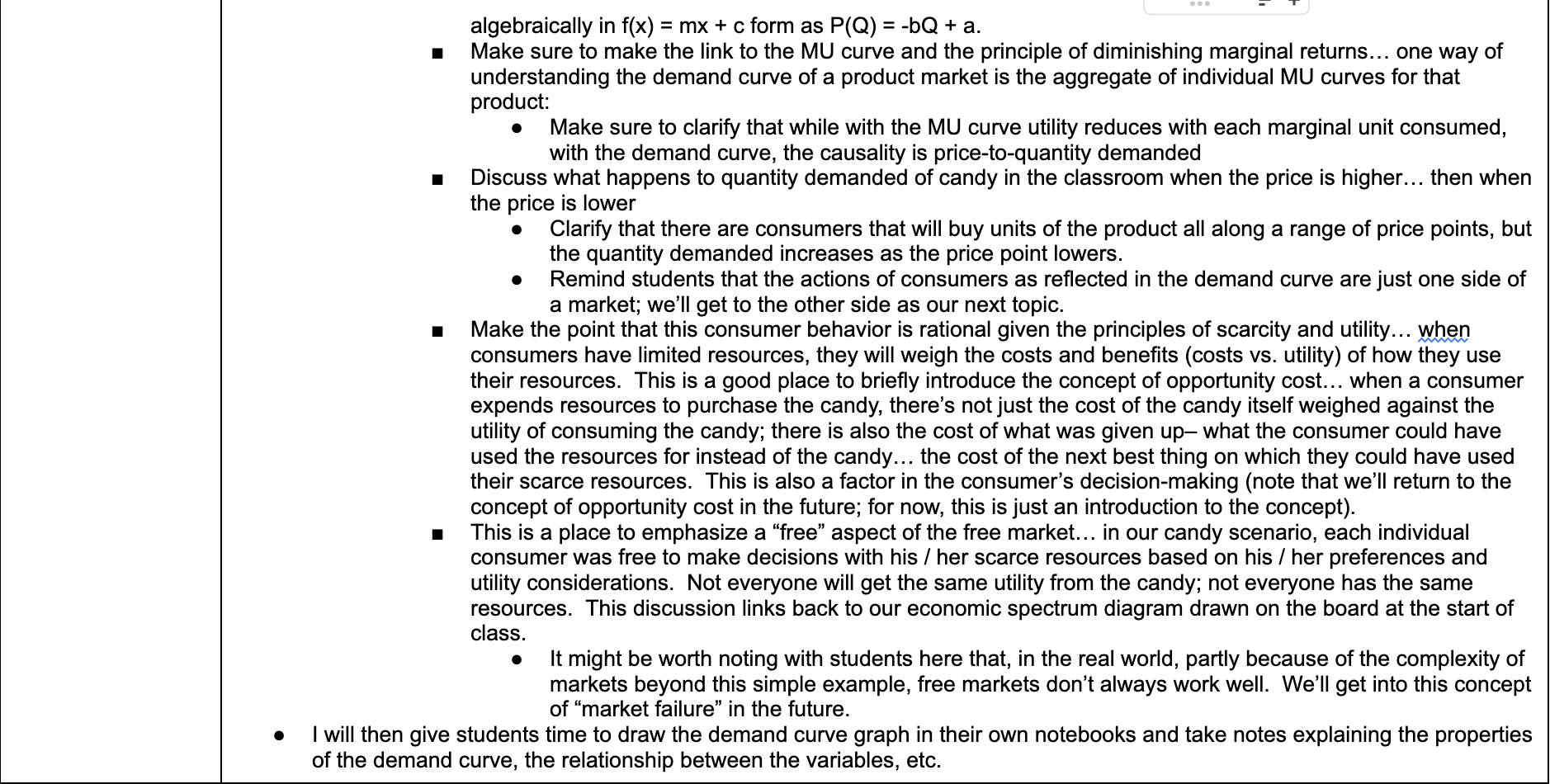

Below I’m going to first provide a blank version of the CoRes tool. I’m then going to provide screenshots and explanations of each line of my example.

The CoRes Tool

Loughran et al. (2004)

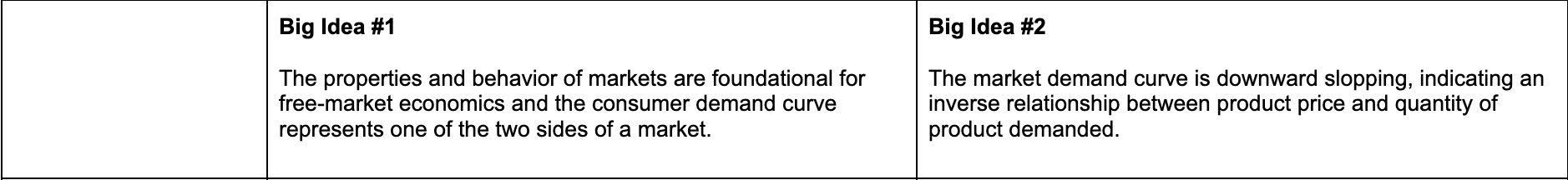

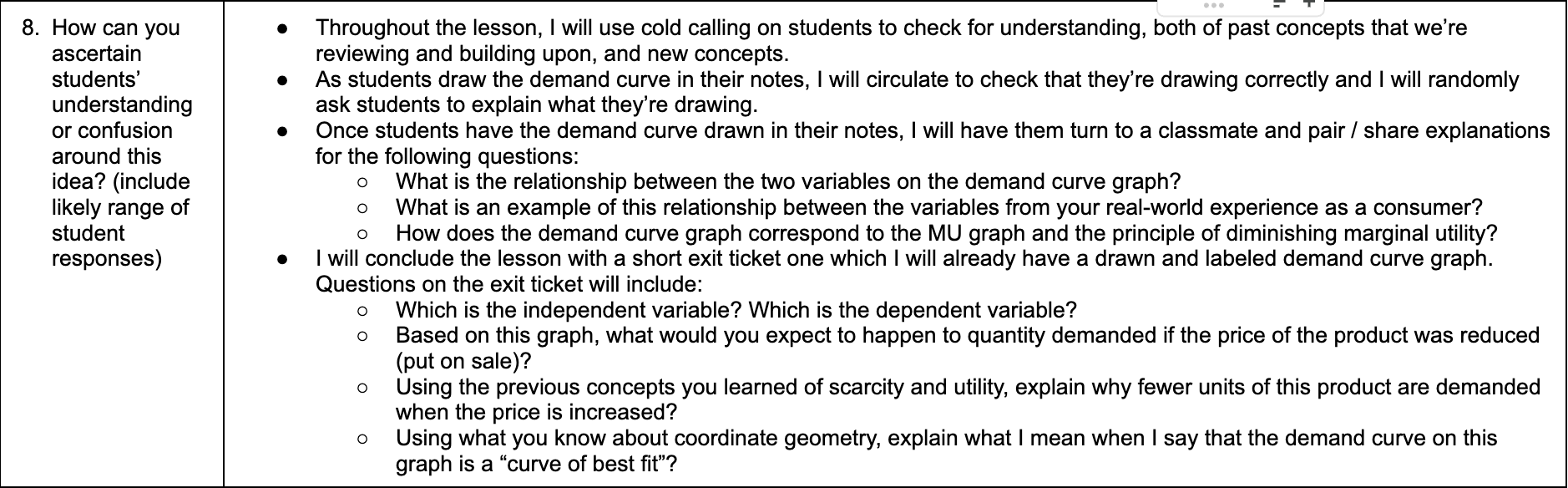

Example CoRes with the Economics Topic of the Market Demand Curve

The first step of the CoRes process is for the teacher to identify the Big Ideas s/he wants the students to understand related to that topic. The template I’ve provided above shows space for two Big Ideas, but a teacher may want to focus on just one for a given topic, or may want to add additional columns for more than two Big Ideas. By “Big Ideas,” Loughran et al. (2004) mean something very much like what Wiggins & McTighe (2011), in their Understanding By Design (UbD) unit-planning model, mean by “Understandings.” These are large, conceptual, and transferable statements. For those familiar with KUDs from Concept-Based Curriculum, these Big Ideas are the “U” of KUDs. If you’re familiar with the Concept-Based Curriculum work of H. Lynn Erickson, you’ll be familiar with her hierarchy of knowledge (Erickson et al., 2017). Individual facts are at the bottom level of the knowledge hierarchy, then multiple facts get organized around concepts at the next level up, and principles are a level above concepts; at the principle level, concepts get combined and generalized into truth statements that transfer beyond the topic to other topics within the discipline, or even to other disciplines. This is the level of Big Ideas. They’re the disciplinary and inter-disciplinary principles the teacher wants the student to understand and carry with them long after they’ve forgotten the other details of the topic. Note that in my example, I chose to focus on Big Ideas that are important within the discipline of economics itself; these are foundational principles that students must understand in order to understand future topics in economics.

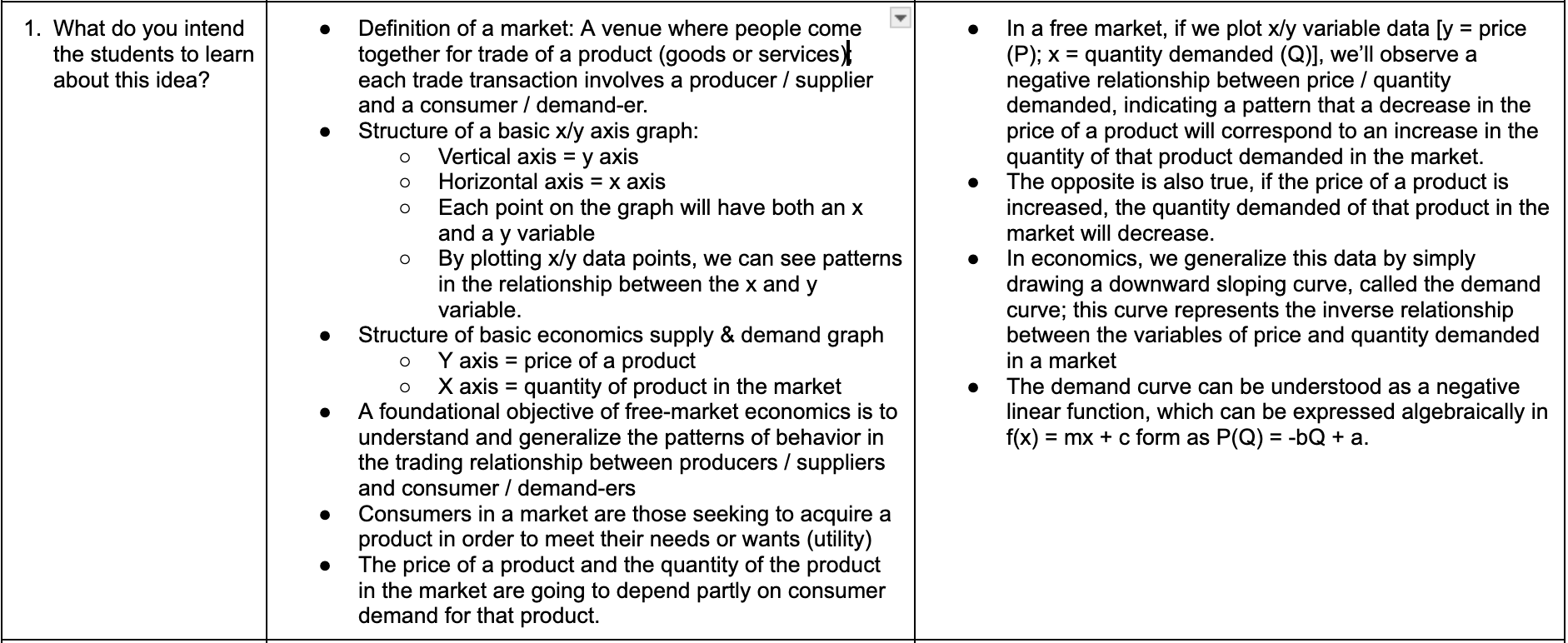

Note that as I provide screenshots below of each line of my example, there will continue to be three columns: the first is the CoRes question, the second responds to the question for Big Idea #1, the third responds to the question for Big Idea #2. In a few cases, I merged my thinking in the example for both Big Ideas at the same time.

The first question asks the teacher to provide details on what the students need to learn in order to understand each of the Big Ideas. There are always more detailed facts, procedures, skills, and concepts that students will need to learn in order to understand the Big Idea. This step forces the teacher to identify these other elements of the topic.

This question requires the teacher to think about the “why” of this topic and it’s Big Ideas. Why is it important for the students to learn what the teacher has listed in #1? How is it required for grasping the Big Idea? Why is it important for future learning in the discipline, or application beyond the discipline? It’s not enough at this point to respond: “Because it’s listed in my curriculum guide.” The teacher needs to ask, why would it be listed in the curriculum guide? Why did the experts who created the curriculum deem this important for students to know?

Note that on this line I found it helpful to merge my thinking and address the question for both Big Ideas at the same time. This question helps the teacher to set boundaries on the topic. For example, at a high school level, there will be elements of many economics topics that will be beyond the scope of an introductory economics course. It helps for the teacher to set these limits so as not to confuse students with elements beyond their level. This question also helps the teacher think about sequencing of topics. In my example, I listed topics and concepts that will follow my teaching of the market demand curve in order to help me think about what students need to understand about this topic to build on it for future topics.

I think this question and the next start to get into the crux of pedagogical reasoning. This question forces the teacher to think about the nature of the topic itself, and the aspects of the topic that are difficult to communicate to students. This could be due to a conceptual challenge within the subject-matter itself, it could have to do with the teaching context, the resources available, or a quirk of the curriculum the teacher is following. It could relate to the students in the room and their background and prior knowledge. You’ll notice from my example that one issue in this topic of the market demand curve, is that price, though it’s the independent variable, by convention within economics, is placed on the y-axis of a graph; this is contrary to the common practice in math, science, and statistics of placing the independent variable on the x-axis. That could be confusing for students; it would help with student understanding if the teacher considered this confusing element in advance and addressed it during the lesson.

This question requires the teacher to ponder student pre-conceptions of the topic. What sort of conceptual understandings do students already have related to this topic, formed either from their personal experience, from other classes or prior grade-levels, or from previous topics they’ve already learned in the class. It’s important that the teacher help students build new learning upon the structure of their prior-knowledge; it’s also important for the teacher to help students correct the conceptions they already have that may only be partial or even misleading.

This question is intentionally quite open. It’s just a space for a teacher to note any other factors that influence the teaching of this topic.

This is the question that requires the teacher to start thinking about the appropriate pedagogical representations and methods for guiding the students to understanding of this topic and its Big Ideas. Because I’ll be teaching the two Big Ideas concurrently with this topic, I chose to merge this into one column. Remember that the CoRes tool is not a lesson plan, so this section doesn’t necessarily contain everything needed for a lesson on this topic. Instead, this question is prompting the teacher to think about the sequence, the examples, the models, the illustrations, etc. that will most effectively help the students grasp the Big Ideas of the topic.

This final question is about formative assessment. It forces the teacher to think about the ways they’ll get glimpses into student thinking throughout the lesson. As Black & Wiliam (1998) point out, student thinking is a “black box” to teachers; teachers cannot see into the minds of students to determine how they’re processing information and forming understandings. The only way a teacher can learn something of student understanding is through formative assessment. Formative assessment does not need to be formal and time-consuming; nor should it be graded. Formative assessment simply refers to the questions the teacher will ask and the tasks the teacher will assign, in order to determine if the students are grasping the topic and the Big Ideas. This question also asks the teacher to anticipate likely student responses. This is to help the teacher think about how to adjust and pivot within the lesson, or for the subsequent lesson, in order to address areas where students only partially understand, or misunderstand some aspect of the topic. The teacher should also consider scenarios where some students understand and are ready to move forward, while others still need further explanation and practice. How will the teacher address this common situation either during the lesson, or in the next lesson?

Personal Take-Aways

Though the topic of the market demand curve is a relatively simple one in economics, I still found this CoRes process quite rewarding. I’ve never been good in the past with helping students connect the market supply and demand graph (or any economics graphs) to their learning about graphs in coordinate geometry and algebra. This process helped me sort out how to do that better in the future. I’ve also sometimes struggled to clearly communicate the relationship between the market demand curve and the marginal utility curve (principle of diminishing marginal utility). Though I understood it myself, I was never good at articulating to students how the demand curve in a product market could be understood as the aggregate of all of the individual consumer marginal utility curves for that product. This CoRes process helped me improve my explanation on that.

This process also helped me analyze some of the student misconceptions I’ve observed during the years of teaching this topic. I hadn’t really thought about the fact that the independent variable (price) on the graph is placed on the y-axis, while the independent variable in other disciplines is typically placed on the x-axis. That could be confusing for students, but I’ve never addressed that in the past. It also helped to think through the common student misunderstanding about causality between the two variables, and how the causality difference between the marginal utility curve and the demand curve could be confusing.

I’ve also never used the candy-jar demonstration for plotting real data using the classroom as a market of consumers for candy. I only came up with that idea as I was thinking through this CoRes tool and deciding how best to demonstrate that the demand curve is a “line-of-best-fit” that represents the behavior of real data plots.

As already noted above, I invested quite a bit of time in this process and included a level of detail that I would rarely have time for in my daily teaching. However, because I invested the time, I think teaching and learning will be improved the next time I approach this topic in class, and I think the time spent with the CoRes tool has helped to strengthen my pedagogical reasoning in general, so that as I think about other topics, I find myself naturally pondering some of these CoRes questions.

I will conclude simply by noting that over the past semester, separate from my research, I have worked with the CoRes tool with several teachers across different high school subject-areas. In that context, because of time restraints, we worked through the tool together for a given topic in a single 45-60 minute session. With that amount of time, we were unable to get to the level of detail I included in my economics example. However, even at a more cursory level, most of the teachers who went through the process with me found it useful for their teaching and for student learning.

References

Black, P. & Wiliam, D. (1998). Inside the black box: Raising standards through classroom assessment. Granda Learning Group.

Erickson, H. L., Lanning, L. A., & French, R. (2017). Concept-based curriculum and instruction for the thinking classroom (Second Edition). Corwin, A SAGE Publishing Company.

Loughran, J., Mulhall, P., & Berry, A. (2004). In search of pedagogical content knowledge in science: Developing ways of articulating and documenting professional practice. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 41(4), 370–391. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20007

Loughran, J., Berry, A., & Mulhall, P. (2012). Understanding and developing science teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge (2nd ed.). Sense Publishers.

Shulman, L. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4–14.

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2011). The Understanding by Design guide to creating high-quality units. Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development.